Nannie Helen Burroughs The Black Goddess of Liberty

Part 8 of 8 In the Suffragists Legacy Series Honoring Women's Right to Vote

Herself360 continues to participate with Suffrage100Ma in commemorating the upcoming 100th Anniversary of the adoption of the 19th Amendment of the Constitution of the United States, which states: “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.”

The journey for women’s rights was difficult and complicated and is not done; the work continues.

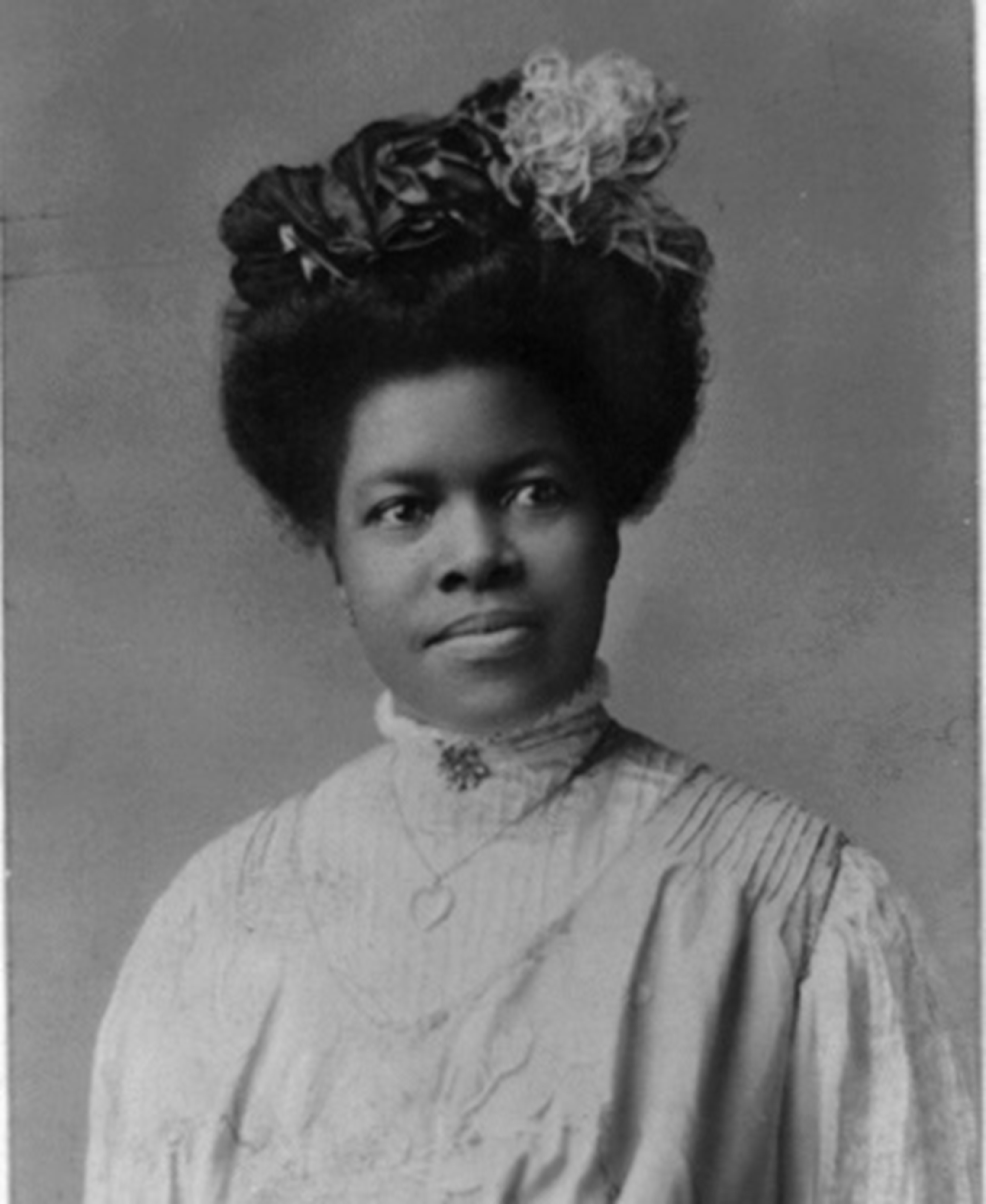

A young Nannie Helen Burroughs.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Quick Facts

SIGNIFICANCE: Educator, activist, suffragist

PLACE OF BIRTH: Orange, VA

DATE OF BIRTH: 1879/1880

PLACE OF DEATH: Washington, DC

DATE OF DEATH:1961

Around 1880, Nannie Helen Burroughs was born to a formerly enslaved couple living in Orange, Virginia. Her father died when she was young, and she and her mother relocated to Washington, DC. Burroughs excelled in school and graduated with honors from M Street High School (now Paul Laurence Dunbar High School). Despite her academic achievements, Burroughs was turned down for a Washington D.C. public school teaching position. Some historians speculate that the elite black community discriminated against Burroughs because she had darker skin. Although, Burroughs' belief in the dignity of manual labor, her strong feminist stance, and insistence on recognizing the poorer, working-class African-Americans as important agents of racial uplift in fact may have contributed to her marginalization as an intellectual.

In her personal and ideological identification with the black working class, Nannie Helen Burroughs resembled the early twentieth-century black community leader Harry Haywood. In her outspoken militant defense of the black race, particularly black women, the race-conscious Burroughs (like Haywood and writer James Baldwin), was committed to "telling the truth" about the "wrongdoings" of white folk and, in her case, about the "white thinking" of members of her own race. (3) It may not have been possible for those who have written about African-American intellectuals to include a woman who was not a college graduate and who so strongly identified with the black working-class. Consistently, she declared: "I swear by my plain people. There are none like them . . . 'nowhere in this country is the situation of the colored man in America more clearly recognized and soundly analyzed than in the homes of the humblest.'" Undeterred, Burroughs decided to open her own school to educate and train poor, working African American women.

Burroughs proposed her school initiative to the National Baptist Convention (NBC). In response, the organization purchased six acres of land in Northeast Washington, D.C. Now Burroughs needed money to construct the school. She did not, however, have unanimous support. Civil rights leader Booker T. Washington did not believe African Americans would donate money to found the school. But Burroughs did not want to rely on money from wealthy white donors. Relying on small donations from black women and children from the community, Burroughs managed to raise enough money to open the National Training School for Women and Girls.

Per the Library of Congress: Nine Afro-American women posed, standing, full length, with Nannie Burroughs holding a banner reading, “Banner State Woman’s National Baptist Convention”

Even though some people disagreed with teaching women skills other than domestic work, the school was popular in the first half of the 20th century. The school originally operated out of a small farmhouse. In 1928, a larger building named Trades Hall was constructed. The hall housed twelve classrooms, three offices, an assembly area, and a print shop.

In addition to founding the National Training School for Women and Girls, Burroughs also advocated for greater civil rights for African Americans and women. At the time, black women had few career choices. Many did domestic work like cooking and cleaning.

As an educator, institution and organization builder, and a major figure in the black church and secular feminist movements, Nanni was one of the best know and well-respected African Americans of the early twentieth century. Burroughs believed women should have the opportunity to receive an education and job training. She wrote about the need for black and white women to work together to achieve the right to vote.

She believed suffrage for African American women was crucial to protect their interests in an often-discriminatory society.

Burroughs died in May 1961. She never married and she devoted her life to the education of black women. In 1964, the school was renamed the Nannie Helen Burroughs School in her honor. Burroughs defied societal restrictions placed on her gender and race and her work foreshadowed the main principles of the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s and 1970s. The Trades Hall, now a National Historic Landmark, is the last physical legacy of her lifelong pursuit for worldwide racial and gender equality.

Sources:

Fitzpatrick, Sandra & Maria R. Goodwin. The Guide to Black Washington: Places and Events of Historical and Cultural Significance in the Nation's Capital. New York: Hippocrene Books, 2001.

Harley, Sharon. "Nannie Helen Burroughs: 'The Black Goddess of Liberty.'" The Journal of Negro History 81, No. 1 (1996): 62-71.

Taylor, Traki L. “'Womanhood Glorified': Nannie Helen Burroughs and the National Training School for Women and Girls, Inc., 1909-1961,” The Journal of African American History 87 (2002): 390-402.

http://www.edwardianpromenade.com/women/fascinating-women-nannie-helen-burroughs/

https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/abs/10.1086/JNHv81n1-4p62?journalCode=jnh

3 For a fuller discussion of Haywood and Baldwin's lives as vindicators of the race, see Franklin, Living Our Stories, Telling Our Truths.

4 Newsclipping, The Afro-American, April 7, 1934, in Nannie Helen Burroughs Collection, Box 331, Library of Congress.

Hidden Washington: The Alley Communities of the Nation’s Capital, Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/loc/kidslc//LGpdfs/hidwash-teacher.pdf