The Civil Rights Activist Murdered by the Ku Klux Klan Whose Story Was Nearly Lost to History

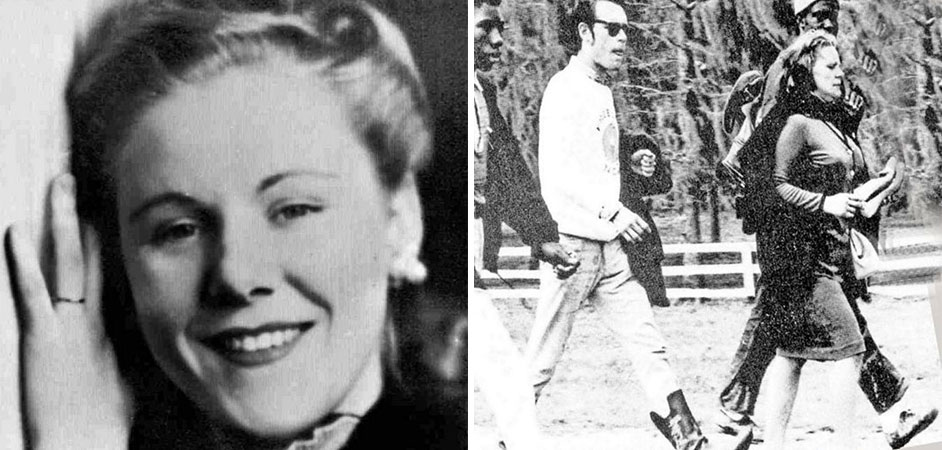

On the final day of the historic Selma to Montgomery March on March 25, 1965, civil rights activist Viola Liuzzo was helping shuttle marchers from Montgomery, Alabama back to Selma in her car, along with a fellow activist, 19-year-old Leroy Moton. When she stopped at a red light, a car filled with local Ku Klux Klan members pulled up alongside them. When they saw Liuzzo, a White woman, and Moton, a Black man, together, they followed them, pulled a gun, and shot directly at Liuzzo. She was killed by a bullet to the head; Moton, who was covered in her blood and knocked unconscious, was assumed to to be dead by the Klan members who investigated the crashed vehicle. The murder of the 39-year-old Liuzzo, a Detroit housewife and mother of five, shocked millions of people around the country and, along with the outrage at the violent treatment of many of the Selma protesters, helped to spur the signing of the historic 1965 Voting Rights Act five months later.

On the final day of the historic Selma to Montgomery March on March 25, 1965, civil rights activist Viola Liuzzo was helping shuttle marchers from Montgomery, Alabama back to Selma in her car, along with a fellow activist, 19-year-old Leroy Moton. When she stopped at a red light, a car filled with local Ku Klux Klan members pulled up alongside them. When they saw Liuzzo, a White woman, and Moton, a Black man, together, they followed them, pulled a gun, and shot directly at Liuzzo. She was killed by a bullet to the head; Moton, who was covered in her blood and knocked unconscious, was assumed to to be dead by the Klan members who investigated the crashed vehicle. The murder of the 39-year-old Liuzzo, a Detroit housewife and mother of five, shocked millions of people around the country and, along with the outrage at the violent treatment of many of the Selma protesters, helped to spur the signing of the historic 1965 Voting Rights Act five months later.

Liuzzo, who had grown up in deep poverty in Tennessee, was already an active member of the Detroit NAACP when she saw television footage of the beating of hundreds of civil rights activists by the Edmund Pettus Bridge during the first attempted march to Selma on March 7, 1965. Horrified by "Bloody Sunday," she decided to heed Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.'s call for volunteers to come to Selma to help in the struggle. Her husband was opposed to her plan, telling her that civil rights "isn't your fight;" she responded that "it's everybody's fight" and drove to Selma to volunteer during the four-day march from Montgomery to Selma. Liuzzo, who called her family nightly with updates, was thrilled by the march's success and to be contributing to what she considered the most important fight of her time.

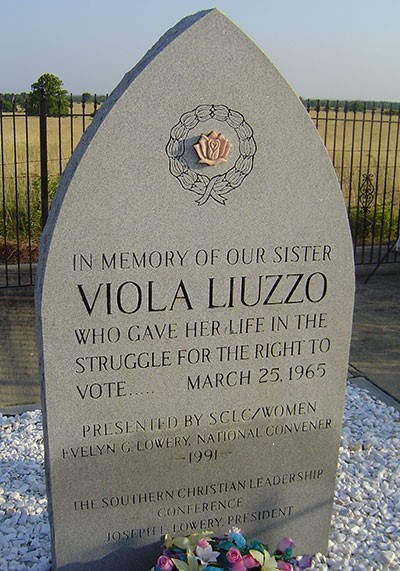

After her death, many prominent civil rights leaders, including King, James Farmer, and Roy Wilkins, attended Liuzzo's funeral in Detroit to pay their respects. The four Klan members were quickly arrested; one of the men was a paid informant for the FBI and protected from prosecution, the other three were found guilty in a federal trial and sentenced to ten years in prison. In an attempt to obscure the fact that an informant was in the car, FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover began a smear campaign to the press directed at Liuzzo, including allegations that she was a drug addict and that she was having an affair with Moton. Hoover and the FBI's role in the smear campaign was uncovered in 1978 when her children obtained FBI case documents under the Freedom of Information Act. Liuzzo's death, the subsequent smear campaign, and the legal fight to uncover the truth are explored in depth in two books: Selma and the Liuzzo Murder Trials: The First Modern Civil Rights Convictions and From Selma to Sorrow: The Life and Death of Viola Liuzzo.

After her death, many prominent civil rights leaders, including King, James Farmer, and Roy Wilkins, attended Liuzzo's funeral in Detroit to pay their respects. The four Klan members were quickly arrested; one of the men was a paid informant for the FBI and protected from prosecution, the other three were found guilty in a federal trial and sentenced to ten years in prison. In an attempt to obscure the fact that an informant was in the car, FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover began a smear campaign to the press directed at Liuzzo, including allegations that she was a drug addict and that she was having an affair with Moton. Hoover and the FBI's role in the smear campaign was uncovered in 1978 when her children obtained FBI case documents under the Freedom of Information Act. Liuzzo's death, the subsequent smear campaign, and the legal fight to uncover the truth are explored in depth in two books: Selma and the Liuzzo Murder Trials: The First Modern Civil Rights Convictions and From Selma to Sorrow: The Life and Death of Viola Liuzzo.

While her story was largely forgotten for many years, Liuzzo's commitment and sacrifice for the pursuit of civil rights has recently received more recognition. In 2017, she was posthumously awarded the Fred L. Shuttlesworth Human Rights Award, an award named in honor of the co-founder of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference which recognizes outstanding individuals who contributed to civil and human rights. And, while the loss of their mother was devastating to her children, they are deeply proud of how she lived her life and the legacy she left. Her daughter Mary Liuzzo Lilleboe says that when they obtained her mother's journal from the FBI, she saw Liuzzo had written "I can’t sit back and watch my people suffer." To Lilleboe, that passage sums up what drove her mother, a devoted Unitarian Universalist, to take action: “She actually believed it when Christ said that the suffering and needy are our people. Mom saw all other human beings as her people.”