Tales of a Neonatal Nurse Practitioner

The Ego Within Us All

The Ego Within Us All

It seems a given that any doctor who is halfway good at his or her job, might develop an inflated ego. Sometimes, however, the ego gets overinflated. Any nurse reading this knows what I’m talking about. It comes with the territory of saving lives and keeping people healthy. But it’s not just doctors – it can happen with nurses, nurse practitioners, EMTs, and anyone who works to save lives.

Several years ago, I was working as a neonatal nurse practitioner in a major medical center where I trained in how to handle different types of high-risk deliveries – from extreme prematurity to post-maturity. Each came with its own set of problems. The hospital handled thousands of deliveries a year – 10% of the babies required the care of the intensive care nursery. This training prepared me to work independently in smaller community hospitals that were affiliated with bigger hospitals. Any kind of pregnant patient could walk through the doors of a community hospital needing help. I was there to provide the necessary care. There, I was a big fish in a small pond – which offered up the potential of developing an inflated ego. However, during the weeks I returned to work in the larger medical center, I was just like all the other little fish, which kept my ego in check.

One Saturday, I was moonlighting in one of the community hospitals, covering the neonatal service. The charge nurse called over the intercom into my office.

“You better come out here. We’ve got a set of twins, born at home, on their way in.” She hung up before I could ask for more information. I grabbed my stethoscope and my well-worn cheat sheet with all the medications and dosages based on weight in kilograms that I might need in a resuscitation. At the nurse’s station, the level of nervous activity and high-pitched chatter sounded an alarm in my head.

“You better come out here. We’ve got a set of twins, born at home, on their way in.” She hung up before I could ask for more information. I grabbed my stethoscope and my well-worn cheat sheet with all the medications and dosages based on weight in kilograms that I might need in a resuscitation. At the nurse’s station, the level of nervous activity and high-pitched chatter sounded an alarm in my head.

“Twins born at home?” I asked the charge nurse. That wasn’t such a big deal. But her reply is what knocked me off kilter. “Yeah,” she answered, “twenty-three weeks.” My heart dropped and my adrenaline surged.

Twenty-three weeks of gestation is the edge of viability. And we weren’t talking just one baby, but twins. What were the odds? I knew the chances of a 23-weeker surviving was around 25% but the odds of having profound neurodevelopmental damage was much higher. It was my job to do everything I could to save them. The developmental repercussions would be sorted out later. None of us is there to play God and decide who should be saved and who shouldn’t.

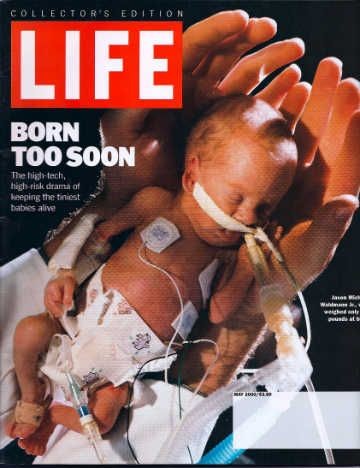

My mind raced through what I needed to do to save these twins. Twenty-three weeks meant each baby was around a pound-and-a-half, maybe two at the most. That’s about the size of a chicken breast you buy at the grocery store. I had helped with resuscitations of 23-weekers plenty of times, at the big house (what we call the main medical center). I knew what needed to be done. I knew how the whole thing should go down, but what should happen and what does happen can be two completely different things. Resuscitating an extremely premature baby as part of a large team of experienced doctors, nurses, and respiratory therapists was one thing. But being the only one who knew what to do, in a distant outlying hospital was another matter completely.

With a deep breath, I rolled a portable warmer and a code cart behind me and called out to two delivery nurses to come with me. Down the elevator, racing down the hall to the ER. I called on my walkie-talkie to the nurse’s station upstairs, telling them to get another warmer down here. The absolute minimal number of people needed to resuscitate a 23-weeker was five – for twins it was ten. I had a team of four – two excellent labor and delivery nurses, a very competent respiratory therapist, and myself. Standing on the sidelines was a small crowd of ER nurses who had never laid eyes on a 23-weeker. I took stock of the situation - I was down six pairs of hands, I was at a community hospital, and the weather forecast was predicting a snowstorm. The odds were quickly stacked against me.

Once in the ER, I checked that the crash cart was fully stocked and up to date, while one of the nurses set up the neonatal warmer, oxygen, and monitoring equipment. The head ER doctor strode over. He proceeded to tell me what was going to happen and basically how I was going to do my job. I laughed. He had no clue what he was talking about. I gave a thirty-second lecture on how, if we wanted to save these babies, they would need the warmth of our neonatal warmers, not the ER stretchers, micro-sized equipment, neonatal doses of drugs, and the neonatal nurses I had with me. Then I smiled at him and returned to what I was doing. Eventually, I would need that doc.

As soon the ER doors flung open, I knew it was show time. The EMTs ran in pushing a transport warmer with the first twin inside. By default, he was named Twin A. He had been born in a toilet at home, probably because Mom’s cervix was too weak to hold onto the babies. There was also the possibility that she’d been using illicit drugs causing premature labor and delivery. Right now, it didn’t matter. What mattered was saving his life. We lifted the baby onto the warmer, floppy and lifeless. With no heart rate, we immediately started resuscitation. As the nurses dried and warmed him, I intubated him (inserted a breathing tube). Cognizant of the risk of a brain hemorrhage I ever so cautiously moved his head to do this. Bleeding happens easily with such frail blood vessels, especially in the head.

As soon the ER doors flung open, I knew it was show time. The EMTs ran in pushing a transport warmer with the first twin inside. By default, he was named Twin A. He had been born in a toilet at home, probably because Mom’s cervix was too weak to hold onto the babies. There was also the possibility that she’d been using illicit drugs causing premature labor and delivery. Right now, it didn’t matter. What mattered was saving his life. We lifted the baby onto the warmer, floppy and lifeless. With no heart rate, we immediately started resuscitation. As the nurses dried and warmed him, I intubated him (inserted a breathing tube). Cognizant of the risk of a brain hemorrhage I ever so cautiously moved his head to do this. Bleeding happens easily with such frail blood vessels, especially in the head.

With my stethoscope on his chest, I listened. He had an intermittent, extremely slow heart rate. I started chest compressions, then gave that job over to one of the neonatal nurses so that I could push a dose of epinephrine down his breathing tube to kick-start his heart. The other nurse started an IV, which was like threading spaghetti-size tubing into a minuscule vein. These nurses were heroes – without an IV the baby could not survive. I calculated the IV rate based on his estimated weight, listened again to his chest, and gave another dose of epinephrine. The respiratory therapist manually ventilated him, ever so carefully in order not to overinflate and pop his fragile lungs. All the while with the stethoscope in one ear, I was constantly reassessing – how was his color? Was his chest moving on inspiration? How was his muscle tone – had it improved at all? What’s his heart rate? His belly was beginning to distend with air from us ventilating him. He needed another tube to decompress his belly to allow for his lungs to inflate. Another dose of Epi, please. Let’s stop chest compression for a minute and see what his heart rate does. It slows but doesn’t stop – an encouraging sign but he still needs another dose of epinephrine. I listened as his heart rate climbed up out of the danger zone. Watching his oxygenation level, I knew it was a fine line between delivering too much oxygen which could cause blindness, and not enough which would starve his brain of oxygen leading to brain damage. There were lab results to respond to – glucose level, if it was too low, he could have a seizure. Hydration level. Given his extreme prematurity his skin was translucent, a source from which he could quickly lose precious fluids, leading to serious dehydration. Still with my stethoscope glued to one ear, and constant monitoring of this little 900-gram (1.9-pound) baby, I couldn’t step away. One of the nurses called the big house to tell them what was going on and that I needed two transport teams STAT. The long-term outcomes of babies born in community hospitals were statistically worse than those born in a hospital with a level III intensive care nursery. These babies were born at home, and while I didn’t know those statistics, obviously they were even worse. Time was of the essence. The nurse held the phone to one of my ears while I kept the stethoscope in my other ear, listening for the steady rhythm of the baby’s heart rate. On the other end of the phone line, the neonatologist was saying, “Listen, we’re getting a transport team together. They’ll be on their way soon. But the snow might be a problem.” Shit. “Are you okay?” he asked from the safe and well-equipped metro hospital twenty miles away. What choice did I have? “Yeah, I’m good,” I answered just as the EMTs rolled in with the second twin.

Twin B rolled in. With one eye on Twin A, alert to any subtle change indicating he needed more oxygen, more epi, and another fluid bolus, I had my other eye and both ears on Twin B and his story. Remarkably he avoided falling into the toilet with his brother and was able to hold on until Mom was in the ambulance en route to the hospital - which is where he decided to be born. The EMT’s did a stellar job at delivering the baby in the ambulance. On arrival, one of the EMTs held an oxygen mask over his face and ventilated him with a resuscitation bag. Right away it was apparent that this twin was smaller and frailer (if that was possible) than his twin brother, indicating that his brother likely received more of the nutrients in utero than he.

His weaker constitution became apparent in the effort it took to keep him alive. No matter how many rounds of epinephrine, how many pumps on his tiny chest with our adult hands, and how many breathing tubes I replaced, he was not going to live. We gave it our all with a full-on resuscitation. Every time we stopped chest compressions his heart would slow to the point that it would stop if we let it. When we stopped ventilating him, he could not resume breathing on his own. I asked the ER doctor to come over so we could talk. I told him that I felt that twenty minutes into the resuscitation and with no spontaneous breaths or heart rate, it was time to call it, to end our efforts and pronounce him dead. Then we could give his mom a few minutes to hold him. I turned to Mom’s gurney, which was only a step away, and explained the full situation: how Twin A was okay and would be transferred to a level III NICU as soon as possible, but that I didn’t think Twin B was going to make it. He was just too little and too premature - we had nothing left to offer to help him. Tears flowed and with incredible strength, she looked at me and nodded.

The ER doc told me to do one more round of everything - meds, chest compressions (which we hadn’t stopped), adjust the breathing tube, and keep ventilating. Images of other babies I had seen who had received “one more try” and had ended up with severe brain damage played over in my head. For this reason, I believed stopping all our efforts was the right thing to do. But truly, who knows when the right time to stop is? Not me. Not the ER doc. Not the neonatologist on his way with the transport team. All we can do is follow the scientific research and make our decisions based on what the research tells us. And our conscience. I never asked to be put in the position of deciding when to stop resuscitating and allow nature to run its course. It was an unwritten and unspoken part of my job description.

We stopped CPR and he died immediately. Twin B had been alive only because we were breathing for him and beating his heart for him. Without that help, he couldn’t survive. I laid him gently in Mom’s arms and went back to Twin A to see how the nurse was doing with him. He looked good! Well, rather, all things considered, he looked okay. The transport team arrived, packed the little guy up, and took him to the big house for specialized neonatal care.

We stopped CPR and he died immediately. Twin B had been alive only because we were breathing for him and beating his heart for him. Without that help, he couldn’t survive. I laid him gently in Mom’s arms and went back to Twin A to see how the nurse was doing with him. He looked good! Well, rather, all things considered, he looked okay. The transport team arrived, packed the little guy up, and took him to the big house for specialized neonatal care.

At the end of the day, after replaying, recapping, and retelling the most unlikely events of 23-week twins born at home and coming to this hospital, I felt good that our team was able to save one of the twins. I couldn’t help but feel proud that we had succeeded in saving a life that started with so many strikes against it.

Fast forward six months. Twin A, who now had a real name, had a corrected age of one month. Even though he had been born six months ago, he was theoretically as young and undeveloped as a one-month-old newborn. Yet he had been born under terrible circumstances and had survived. He’d survived the harsh NICU environment – countless needle sticks, pokes and prodding, the noise, the constant overstimulation all day and night, endless tests, interventions, and surgical procedures to keep him alive. Medications, pumped breastmilk mixed with fortified preemie formula, head scans, heart echocardiograms, mechanical ventilation for weeks – his little system was bombarded with the harsh world of the NICU, just to keep him alive.

Then the day came to start planning for his discharge home. He would be going home on continuous oxygen and monitoring and fed through a gastric tube while therapists continued to work with his physical development.

I knew the chances were high that he would be developmentally challenged. Nonetheless, it was a crushing blow to hear just how challenged he was at the time of discharge. Would he and his family be better off if he hadn’t survived? It was going to cost his community and society millions of dollars to provide him with the support he needed. There would be endless hours of stress and heartache for Mom and any of his caregivers. What had it all been for? Screw the pride, forget the ego – I felt I did this little baby no favors.

I continued for years afterward in my job as an NNP. Not to feed my ego, not to be heroic in saving barely viable lives. But because of the many miraculous births and babies, who, against the odds survived stronger and healthier than anyone thought possible. And for the thousands of parents who desperately wanted a child and were able to take their baby home.

To read more of Julie’s writing, go to https://juliehatch.substack.com/