What Challenges Have You Allowed to Define You?

What challenges have you allowed to define you? How could you change the story?

What challenges have you allowed to define you? How could you change the story?

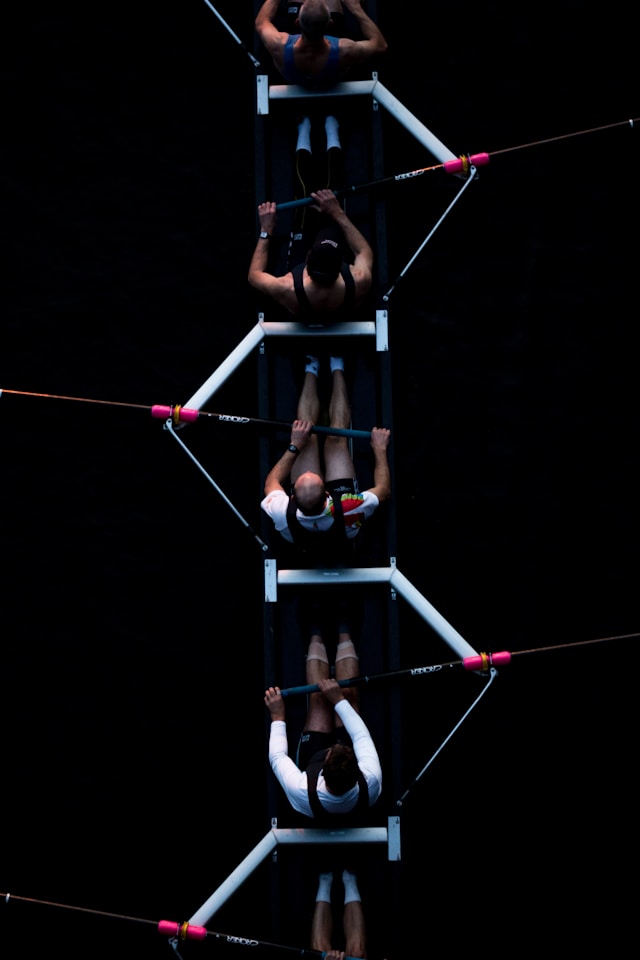

One of the brightest stars of the recent 2024 Olympics was American sprinter Noah Lyles. Lyles, a 27-year-old known for his exuberant style on the track, won gold in the 100 meters in a photo finish, earning the title of “fastest man in the world”

Lyles punctuated his gold medal win with a notable social media post, writing:

"I have Asthma, allergies, dyslexia, ADD, anxiety and Depression. But I will tell you that what you have does not define what you can become. Why Not You!"

Like many, Lyles overcame extraordinary physical and mental hardships to reach the top of his field. But you’d never know it when you watch him race, and that’s a lesson many people today need to embrace.

Lyles first opened up about his mental health challenges at the 2021 Olympics in Tokyo, Lyles’ brother failed to qualify, dashing a dream the two sprinters had of competing together. Lyles, despite being heavily favored to win the 200 meters, took bronze. Afterward, he sobbed to reporters, opening up about his mental health struggles and how devastated he was to compete without his brother.

This was an inflection point in Lyles’ life that could have sent him down a very different path. However, he reclaimed the gold in the 200 meters in the 2022 and 2023 World Championships and won the 100 meters at the 2023 World Championships and 2024 Olympics. Lyles’ resurgence was due in part to his refusal to allow his mental struggles to overshadow his incredible talent and ability.

The nature of mental health care and dialogue has transformed immensely over the past several years. It’s undeniably positive that we’ve increased awareness of mental health issues and removed the stigma surrounding them. However, too many people with mental illnesses, learning disabilities or physical challenges are quick to define themselves by those struggles, often with encouragement from parents, teachers, and counselors. This tendency is amplified by our social media environment, where talking openly about our challenges is rewarded with engagement and virality.

Lyles acknowledged his challenges openly; however, he also refused to be defined by them and rose above them on the world stage. Today, it feels like we have too many people doing the former, without achieving the latter.

Dr. Abigail Shrier, author of one of the best books I’ve read this year, Bad Therapy, talks about this phenomenon in detail. In particular, she shares a story in her book about a father who proudly posted on social media about their child getting into an elite school. The father posted:

Dr. Abigail Shrier, author of one of the best books I’ve read this year, Bad Therapy, talks about this phenomenon in detail. In particular, she shares a story in her book about a father who proudly posted on social media about their child getting into an elite school. The father posted:

“It’s quite something that this dyslexic kid who had trouble early on in school got to high school and really exceeded everyone’s expectation, including, I dare say his own”

This framing is both condescending and disempowering. As Dr Shrier notes, you would never introduce your child, friend, or partner to someone by talking about their weaknesses. And yet, when our current dialogue encourages people to consistently center their challenges, their struggles will define them.

Lyles did not let his worst hardships doom his athletic career. Instead, he received treatment, worked tirelessly, rebuilt his confidence, and became what he always dreamed of being: an Olympic champion and the best in the world.

Lyles’ story—and his framing of strengths and weaknesses—has clear applications in both parenting and leadership:

Lyles’ story—and his framing of strengths and weaknesses—has clear applications in both parenting and leadership:

- For Parents: Find the proper balance between giving children space to talk about their weaknesses or challenges and not allowing those issues to define them. Remind them that hardships are an often-necessary part of the journey to success, that struggle is something to be embraced, not feared, and that while you cannot control what challenges you face, you can control your response and define your life story accordingly.

- For Leaders: You’ll have people on your team who make significant mistakes, experience doubt, and find they don’t excel at certain things, no matter how hard they try to improve. Help team members focus on what they’re excellent at, give them projects and roles that align with their strengths, and minimize their weaknesses.

Nothing great is ever achieved with a victim mindset. Lyles ultimately beat his demons by showing resilience, doubling down on what he was already great at, throwing himself into his training, and using the fruits of that labor to rebuild his confidence. It paid off in gold.

What challenges have you allowed to define you? How could you change the story?

Quote of The Week

"You may not control all the events that happen to you, but you can decide not to be reduced by them.” -Maya Angelou

Follow me on Twitter, Instagram or LinkedIn or reach out anytime.

Photo of Noah Lyles courtesy of his Facebook Page