Trending 5-23-2018

First African American Woman In The Nation Wins Gubernatorial Nomination

Washington (CNN) Stacey Abrams will win the Democratic primary in Georgia's gubernatorial race Tuesday, CNN projects, becoming the first black woman in the nation to hold a major party's nomination for governor. If she wins in November, she will become the country's first black female governor.

Washington (CNN) Stacey Abrams will win the Democratic primary in Georgia's gubernatorial race Tuesday, CNN projects, becoming the first black woman in the nation to hold a major party's nomination for governor. If she wins in November, she will become the country's first black female governor.

The former state House minority leader defeated former state Rep. Stacey Evans, who ran a campaign that tried to appeal to moderates and independent voters.

Abrams, who grew up in Gulfport, Mississippi, as one of six children, told CNN's Kyung Lah in an interview before the election she was aware that "as an African-American woman, I will be doing something no one else has done."

In the interview, Abrams also recounted a story about being rejected as a high school student at the gates of the Georgia Governor's Mansion at an event honoring the state's top students.

"In front of the most powerful place in Georgia, telling me I don't belong there, that's resonated for me for the last 20 years. The reality is having a right to

Abrams' status as an African-American with strong progressive support, as well as Georgia's status as an early primary and marquee general election state, made her campaign a major draw for national Democratic figures.

Hillary Clinton and Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders endorsed Abrams, and New Jersey Sen. Cory Booker and California Sen. Kamala Harris went to Georgia to campaign for her.

The Republican race, meanwhile, could be headed to a runoff, with none of the six candidates -- including Lt. Gov. Casey Cagle and secretary of state Brian Kemp -- currently holding a majority of the vote.

If no candidate tops 50%, the top two will advance to a one-on-one runoff on July 24 to decide who will take on Abrams.

CNN's Kyung Lah contributed to this report.

Monica Lewinsky Gives a Lesson On How To Reclaim Your Power

You are invited to an event, and then the organizers tell you that you are no longer invited. This is what happened to anti-bullying activist Monica Lewinsky who became famous for having a relationship with President Bill Clinton while she was a White House intern and then was publicly ridiculed for the scandal. The magazine Town & Country invited her to an event and then sidelined her when they realized Bill Clinton was attending.

Lewinsky was not about to allow them to have the last word. She responded to the “social dis” and gave a lesson on how to reclaim your power.

Whether you have been excluded from speaking or sidelined at a meeting, you can maintain your value. Here are three steps to reclaiming your power:

1. Call out a bad move to prevent it from happening again.

Lewinsky tweeted what happened.

She wasn’t finished going public. Lewinsky then wrote an article in Vanity Fair about the situation. “It’s 2018, people. I stood up and called B.S. publicly,” she said in the article.

If you have or know someone who has been excluded, say something. You have to call out the wrong so that it does not happen again. The outcome may be worse for repeatedly being excluded than speaking up after the first instance. Tell the person who sidelined you. If you cannot tell that person, tell an advocate or champion of yours. If you cannot speak, tell someone who can speak on your behalf.

2. Admit to yourself that you have been sidelined.

Lewinsky was like most people would be, unhappy about being disinvited. No one wants to be excluded, especially when you were initially included. (A “sorry but not sorry” moment for the event organizers that ended up being a big mistake in the end.) No one wants to be sidelined. A man who society assumes wields more power (because he is a man and former U.S. president, which have all been men) took away Lewinsky’s power, for a moment. (Reminder: The world’s power is not a zero-sum game.)

Lewinsky was like most people would be, unhappy about being disinvited. No one wants to be excluded, especially when you were initially included. (A “sorry but not sorry” moment for the event organizers that ended up being a big mistake in the end.) No one wants to be sidelined. A man who society assumes wields more power (because he is a man and former U.S. president, which have all been men) took away Lewinsky’s power, for a moment. (Reminder: The world’s power is not a zero-sum game.)

To reclaim your power, recognize what has been taken from you. It is okay to feel

3. Recognize and own your value in the world.

Lewinsky knew her value and power. In knowing her value, she recognized the unfairness of the “

She also knew that what happened to her was trivial but indicative of a greater societal problem that needed attention. What happened to Lewinsky shined a light on another example of the imbalance of power between men and women and widespread marginalization of women in society.

“On the spectrum of world injustices, I recognize fully, the act of receiving an invitation to a philanthropy summit and then having it revoked doesn’t even rate. However, in a time when society is struggling to address issues of power and inclusion, maybe it is worth examining,” Lewinsky shares in her article.

She continues: “[Un]derneath it all, there were some interesting lessons in outmoded power structures, in outdated ways of thinking and modeling behavior, in the evolving definitions of inclusion—and in the ramifications that come when you deliberately choose to exclude.”

Lewinsky saw the faux pas done to her as an “opportunity to move this very important conversation forward.” She leveraged the opportunity to advocate not only for herself but others, too. This was an opportunity to empower other women to call out wrongs being done to them. Lewinsky showed the world her power.

Silence protects the status quo. Speak up to ensure a better future for you and all those who have been sidelined. When you advocate for yourself, you have the opportunity to advocate for others and better the circumstances for all. When you speak up for others, you can multiply your power and the power of all women.

Avery

Low-Paid Women Get Hollywood Money to File Harassment Suits

By Michael Corkery, New York Times

Gina Pitre had come to dread working at Walmart. A manager, she said, used to touch her inappropriately and make suggestive comments. Ms. Pitre, 56, who earned $11.50 an hour fulfilling online orders in D’Iberville, Miss., said she felt degraded and angry.

Gina Pitre had come to dread working at Walmart. A manager, she said, used to touch her inappropriately and make suggestive comments. Ms. Pitre, 56, who earned $11.50 an hour fulfilling online orders in D’Iberville, Miss., said she felt degraded and angry.

Ms. Pitre saw a television news segment this winter about how female Hollywood stars and producers had started Time’s Up, a group to help women combat harassment. A related initiative, the Time’s Up Legal Defense Fund, connected Ms. Pitre with a lawyer and is helping fund her lawsuit against Walmart and one of its managers.

Hollywood, it appears, is starting to make good on its promise to focus on women outside the limelight and broaden the #MeToo movement. Filed last month, the lawsuit, one of the first to arise from the Time’s Up fund, is part of a multipronged approach. Beyond the various legal aspects, the group is working with labor and social activists, as well as communications specialists and others, to publicize the struggles of working women facing harassment on the job.

The actress Susan Sarandon, along with Ms. Pitre, female Walmart workers, and labor activists, signed a letter to the retailer’s chief executive, demanding changes in the company’s policies and procedures around harassment. “I don’t care who you are,” said Ms. Pitre, who left her job at Walmart last month. “There is no cause for disrespect.”

In a statement, Walmart said it had conducted a “comprehensive investigation” into Ms. Pitre’s complaints and “could not substantiate a violation of our Discrimination and Harassment Prevention Policy.”

“We do not tolerate discrimination or harassment of any kind and thoroughly investigate all sexual harassment allegations,” the statement added.

Since its launch in January, the Time’s Up fund — which is administered by the National Women’s Law Center in Washington — has raised about $22 million in donations to help pay for legal representation and other assistance for women facing harassment.

So far, about 2,700 workers have contacted the fund, saying they have been harassed. The largest number of complaints, about 9 percent, have come from the arts industry, followed by workers in the federal government, education, and healthcare. Retail workers made roughly 5 percent of the complaints.

Volunteers at the National Women’s Law Center, an advocacy group focused on women’s rights, have been reviewing the online complaints and providing many workers with names of lawyers who might be willing to take on their case. The law center does not vet the facts of each case but relies on the workers’ lawyers to make sure the claims are sound.

When deciding on funding, the staff uses a set of “priorities,” including whether the worker is in a low-wage job or in a male-dominated occupation.

“We hope to send a message to employers,” said Emily Martin, the law center’s general counsel. “Just because a woman doesn’t have a lot of money or connections doesn’t mean someone isn’t going to stand up for them.”

The assistance from Time’s Up is relatively modest — about $3,000 to help pay the initial lawyer fees. If the case goes to trial, the fund will provide up to $100,000 for fees.

The money is meant to help defray some of the financial risks that lawyers face when taking a harassment case. Lawyers typically work on a contingency basis — meaning they are paid only if there is a settlement or they are successful at trial. Even then, some damages are capped in federal court, and judges in certain states may be inclined to rule against plaintiffs.

Ms. Martin said it was difficult to track how many lawsuits had arisen from the Time’s Up campaign in the roughly five months since it was started.

One of the early lawsuits was filed by a medical resident who said she had been forced out of her program after reporting harassment. Ms. Martin said the woman did not want her name disclosed.

In some cases, publicity is part of the strategy. The National Women’s Law Center will provide “communications support” — connecting women with public relations specialists — to help them call attention to their story.

Ms. Martin said publicity could help “broaden the impact” of the legal cases in combating harassment. Toward that end, the law center connected Ms. Pitre with Our Walmart, a worker advocacy group. This month, Our Walmart sent the letter signed by Ms. Pitre and Ms. Sarandon to Walmart’s chief executive, Doug McMillon, calling on the retailer to revamp its harassment procedures.

A Walmart spokesman said in a statement, “We have strong policies and procedures in place to address allegations of sexual harassment, and we believe our current practices meet or exceed many of the requests in the letter.”

When Ms. Pitre started working at Walmart in June 2016, she liked the job, she said. But after a few months, a supervisor started to harass her, including instances when he grabbed her breasts and made “unwelcome sexual comments,” according to her lawsuit.

Last July, she reported the harassment to a company ethics department, her lawsuit says. Ms. Pitre said she was eventually told that the company’s investigation was closed, but was never told the outcome.

A Walmart spokesman said the company does not disclose the outcomes of its harassment investigations to anyone, including the employee filing the complaint. The spokesman said this policy is aimed at the “privacy and confidentiality of all concerned.”

In its letter, Our Walmart demands that the company start informing employees about the results of its harassment investigations.

Ms. Pitre had previous experience with harassment. In 2008, she filed a lawsuit in federal court, accusing her former managers at the Boomtown Casino in Biloxi, Miss. of groping her and making sexually suggestive comments, according to her lawsuit.

The case resulted in a confidential settlement and “the termination and/or discipline of certain parties at Boomtown Casino,” a company spokesman said in an email.

Ms. Martin said she was not aware of Ms. Pitre’s earlier lawsuit when the Time’s Up fund approved funding for her Walmart case. But Ms. Martin said it would not have been a factor in the decision.

“It is not shocking that this job is not the first job where Gina has experienced some sort of harassment,” Ms. Martin said.

The Jackson, Miss., office of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission said it had been “unable to conclude” that the “information obtained” in Ms. Pitre’s case showed that Walmart had broken the law. The agency added that its ruling did not mean Walmart was “in compliance with the statutes,” either.

Ms. Pitre had hired a previous lawyer, but parted ways with her after, she said, the lawyer was hesitant about pursuing a case against Walmart.

The National Women’s Law Center put Ms. Pitre in touch with Louis H. Watson Jr., who has had success with harassment claims. A few years ago, he represented a group of female firefighters who said they faced unwanted advances and crude taunts by male supervisors in Jackson. After a jury found in the women’s favor, the city agreed to pay them tens of thousands of dollars each and improve its harassment policies.

Still, harassment cases face an uphill battle in places like Mississippi, Mr. Watson said. “It is such a conservative state,” he said. “There are not many lawyers who want to take on these claims.”

Pulitzer Prize-Winning Author, Philip Roth, Dies at 85

NEW YORK — Philip Roth, the prolific,

NEW YORK — Philip Roth, the prolific,

His death was confirmed by Judith Thurman, a close friend.

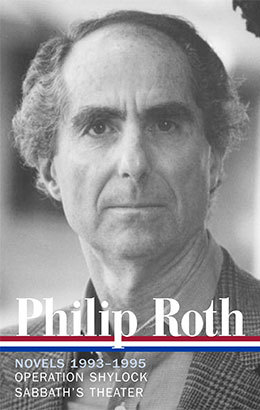

Mr. Roth was the last of the great white males: the triumvirate of writers — Saul Bellow and John Updike were the others — who towered over American letters in the second half of the 20th century. Outliving both and borne aloft by an extraordinary second wind, Mr. Roth wrote more novels than either of them. In 2005 he became only the third living writer (after Bellow and Eudora Welty) to have his books enshrined in the Library of America.

“Updike and Bellow hold their flashlights out into the world, reveal the world as it is now,” Mr. Roth once said. “I dig a hole and shine my flashlight into the hole.”

The Nobel Prize eluded Mr. Roth, but he won most of the other top honors: two National Book Awards, two National Book Critics Circle awards, three PEN/Faulkner Awards, a Pulitzer Prize and the Man Booker International Prize.

In his 60s, an age when many writers are winding down, he produced an exceptional sequence of historical novels — “American Pastoral,” “The Human Stain,” and “I Married a Communist” — a product of his personal reengagement with America and American themes. And starting with “Everyman” in 2006, when he was 73, he kept up a relentless book-a-year pace, publishing works that while not necessarily major were nevertheless fiercely intelligent and sharply observed. Their theme in one way or another was the ravages of age and mortality itself, and in publishing them Mr. Roth seemed to be defiantly staving off his own decline.

Mr. Roth was often lumped together with Bellow and Bernard Malamud as part of the “Hart, Schaffner & Marx of American letters,” but he resisted the label. “The epithet American-Jewish writer has no meaning for me,” he said. “If I’m not an American, I’m nothing.”

Mr. Roth was often lumped together with Bellow and Bernard Malamud as part of the “Hart, Schaffner & Marx of American letters,” but he resisted the label. “The epithet American-Jewish writer has no meaning for me,” he said. “If I’m not an American, I’m nothing.”

And yet, almost against his will sometimes, he was drawn again and again to writing about themes of Jewish identity, anti-Semitism and the Jewish experience in America. He returned often, especially in his later work, to the Weequahic neighborhood of Newark, where he grew up and which became in his writing a kind of vanished Eden: a place of middle-class pride, frugality, diligence

It was a place where no one was unaware “of the power to intimidate that emanated from the highest and lowest reaches of gentile America,” he wrote, and yet where being Jewish and being American were practically indistinguishable. Speaking of his father in “The Facts,” an autobiography, Mr. Roth said: “His repertoire has never been large: family, family, family, Newark, Newark, Newark, Jew, Jew, Jew. Somewhat like mine.”

Mr. Roth’s favorite vehicle for exploring this repertory was himself, or rather one of several fictional alter egos he deployed as a go-between, negotiating the tricky boundary between autobiography and invention and deliberately blurring the boundaries between real life and fiction. Nine of Mr. Roth’s novels are narrated by Nathan Zuckerman, a novelist whose career closely parallels that of his creator. Three more are narrated by David Kepesh, a

The protagonist of “Operation Shylock” is a character named Philip Roth, who is being impersonated by another character, who has stolen Roth’s identity. At the center of “The Plot Against America,” a book that invents an America where Charles Lindbergh wins the 1940 presidential election and initiates a secret pogrom against Jews, is a New Jersey family named Roth that resembles the author’s in every particular.

“Making fake biography, false history, concocting a half-imaginary existence out of the actual drama of my life is my life,” Mr. Roth told Hermione Lee in a 1984 interview in The Paris Review. “There has to be some pleasure in this life, and that’s it.”

Occasionally, as in “Deception,” a slender 1990 novel about a writer named Philip who is writing about a writer having an affair with one of his made-up characters, this sleight of hand feels stuntlike and a little dizzying. More often, and especially in “The Counterlife” (1986), Mr. Roth’s masterpiece in this vein, what results is a profound investigation into the competing and overlapping claims of fiction and reality, in which each aspires to the condition of the other and the very idea of a

Mr. Roth’s other great theme was sex, or male lust, which in his books is both a life force and a principle of rage and disorder. It is sex, the uncontrollable need to have it, that torments poor, guilt-ridden Portnoy, probably Mr. Roth’s most famous character, who desperately wants to “be bad — and to enjoy it.” And Mickey Sabbath, the protagonist of “Sabbath’s Theater,” one of Mr. Roth’s major late-career novels, is in many ways Portnoy grown old but still in the grip of lust and longing, raging against the indignity of old age and yet saved from suicidal impulses by the realization that there are too many people he loves to hate.

Mr. Roth’s other great theme was sex, or male lust, which in his books is both a life force and a principle of rage and disorder. It is sex, the uncontrollable need to have it, that torments poor, guilt-ridden Portnoy, probably Mr. Roth’s most famous character, who desperately wants to “be bad — and to enjoy it.” And Mickey Sabbath, the protagonist of “Sabbath’s Theater,” one of Mr. Roth’s major late-career novels, is in many ways Portnoy grown old but still in the grip of lust and longing, raging against the indignity of old age and yet saved from suicidal impulses by the realization that there are too many people he loves to hate.

In public, Mr. Roth, tall and good-looking, was gracious and charming but with little use for small talk. In private he was a gifted mimic and comedian. Friends used to say that if his writing career had ever fizzled he could have made a nice living doing stand-up. But there was about his person, as about his writing, a kind of simmering intensity, an impatience with art that didn’t take itself seriously.

Some writers “pretend to be more lovable than they are and some pretend to be less,” he told Ms. Lee. “Beside the point. Literature isn’t a moral beauty contest. Its power arises from the authority and audacity with which the impersonation is pulled off; the belief it inspires is what counts.”

Philip Milton Roth was born in Newark on March 19, 1933, the younger of two sons. (His brother, Sandy, a commercial artist, died in 2009.) His father, Herman, was an insurance manager for Metropolitan Life who felt that his career had been thwarted by the gentile executives who ran the company. Mr. Roth once described him as a cross between Captain Ahab and Willy Loman. His mother, the former Bess Finkel, was a secretary before she married and then became a housekeeper of the heroic old school — the kind, he once suggested, who raised cleaning to an art form.

The family lived in a five-room apartment on Summit Avenue within which were only three books when he was growing up — given as presents when someone was ill, Mr. Roth said. He went to Weequahic High, where he was a good student but not good enough to win a scholarship to Rutgers, as he had hoped. In 1951 he enrolled as a pre-law student at the Newark branch of Rutgers, with vague notions of becoming “a lawyer for the underdog.”

The family lived in a five-room apartment on Summit Avenue within which were only three books when he was growing up — given as presents when someone was ill, Mr. Roth said. He went to Weequahic High, where he was a good student but not good enough to win a scholarship to Rutgers, as he had hoped. In 1951 he enrolled as a pre-law student at the Newark branch of Rutgers, with vague notions of becoming “a lawyer for the underdog.”

But he yearned to live away from home, and the following year he transferred to Bucknell College in Lewisburg, Pa., a place about which he knew almost nothing except that a Newark neighbor seemed to have thrived there. Inspired by one of his professors, Mildred Martin, with whom he remained a lasting friend, Mr. Roth switched his interests from law to literature. He helped found a campus literary magazine,

Mr. Roth graduated from Bucknell, magna cum laude, in 1954 and won a scholarship to the University of Chicago, where he was awarded an M.A. in 1955. That same year, rather than wait for the draft, he enlisted in the Army but suffered a back injury during basic training and received a medical discharge. In 1956 he returned to Chicago to study for a Ph.D. in English but dropped out after one term.

Mr. Roth had begun to write and publish short stories by then, and in 1959 he won a Houghton Mifflin Fellowship to publish what became his first collection, “Goodbye, Columbus.” It won the National Book Award in 1960 but was denounced — in an inkling of trouble to come — by some influential rabbis, who objected to the portrayal of the worldly, assimilated Patimkin family in the title novella, and even more to the story “Defender of the Faith,” about a Jewish Army sergeant plagued by goldbricking draftees of his own faith.

In 1962, while appearing on a panel at Yeshiva University, Mr. Roth was so denounced, for that story especially, that he resolved never to write about Jews again. He quickly changed his mind.

“My humiliation before the Yeshiva belligerents — indeed, the angry Jewish resistance that I aroused virtually from the start — was the luckiest break I could have had,” he later wrote. “I was branded.”

Mr. Roth later called his first two novels “apprentice work.” “Letting Go,” published in 1962, was derived in about equal parts from Bellow and Henry James. “When She Was Good,” which came out in 1967, is the most un-Rothian of his books, a Theodore Dreiser- or Sherwood Anderson-like story set in the WASP Midwest in the 1940s.

“When She Was Good” was based in part on the life and family of Margaret Martinson Williams, with whom Mr. Roth had entered a calamitous relationship in 1959. Ms. Williams, who was divorced and had a daughter, met Mr. Roth while she was waiting tables in Chicago, and she tricked him into marriage by pretending to be pregnant. He was “enslaved” to her own sense of victimization, he wrote. They separated in 1963, but Ms. Williams refused to divorce, and she remained a vexatious presence in his life until she died in a car crash in 1968. (She appears as Josie Jensen in “The Facts” and, more or less undisguised, as the exasperating Margaret Tarnopol in Mr. Roth’s novel “My Life as a Man.”)

After the separation, Mr. Roth moved back East and began work on “Portnoy’s Complaint,” the novel for which he may be best known and which surely set a record for most masturbation scenes per page. It was a breakthrough not just for Mr. Roth but for American letters, which had never known anything like it: an extended, unhinged monologue, at once filthy and hilarious, by a neurotic young Jewish man trying to break free of his suffocating parents and tormented by a longing to have sex with gentile women, shiksas.

The book was “an experiment in verbal exuberance,” Mr. Roth said, and it deliberately broke all the rules.

The novel, published in 1969, became a best seller but received mixed reviews. Josh Greenfeld, writing in The New York Times Book Review, called it “the very novel that every American-Jewish writer has been trying to write in one guise or another since the end of World War II.” On the other hand, Irving Howe (on whom Mr. Roth later modeled the pompous, stuffy critic Milton Appel in “The Anatomy Lesson”) wrote in a lengthy takedown in 1972, “The cruelest thing anyone can do with ‘Portnoy’s Complaint’ is read it twice.”

And once again the rabbis complained. Gershom Scholem, the great Kabbalah scholar, declared that the book was more harmful to Jews than “The Protocols of the Elders of Zion.”

Mr. Roth’s autobiographical phase began in 1974 with “My Life as a Man,” which he said was probably the least factually altered of his books, and continued with the Zuckerman trilogy — “The Ghost Writer” (1979), “Zuckerman Unbound” (1981) and “The Anatomy Lesson” (1983) — which examined the authorial vocation and even the nature of writing itself.

Zuckerman reappeared in “The Counterlife” (1986), where he seems to die of a heart attack and is then resurrected. “Operation Shylock” (1993), which Mr. Roth pretended was a “confession,” not a novel (though in the very last sentence he says, “This confession is false”), involved two Roths, one real and one phony, and the real one claims to have been a spy for the Mossad. The book, with its sense of shifting reality and unstable identity, partly stemmed from a near-breakdown Mr. Roth experienced when he became addicted to the sleeping pill Halcion after knee surgery in 1983 and from severe depression he suffered after emergency bypass surgery in 1989.

For much of this time, Mr. Roth had been spending half the year in London with the actress Claire Bloom, with whom he began living in 1976. They married in 1990 but divorced four years later. In 1996, Ms. Bloom published a memoir, “Leaving the Doll’s House,” in which she depicted him as a misogynist and control freak, so self-involved that he refused to let her daughter, from her marriage to the actor Rod Steiger, live with them because she bored him.

Never fond of attention, Mr. Roth became even more private after this accusation and never publicly replied to it, though some critics found unflattering parallels to Ms. Bloom and her daughter in the characters Eve Frame and her daughter, Sylphid, in “I Married a Communist.”

The marriage over, Mr. Roth moved permanently back to the United States and began what proved to be the third major phase of his career. He returned, he said, because he felt out of touch: “It was really my rediscovering America as a writer.”

“Sabbath’s Theater,” which came out in 1995 and won the National Book Award, is about neither Roth nor Zuckerman but rather Morris Sabbath, known as Mickey, an ex-puppeteer in his 60s. His voice is nothing if not American: an angry, comic, lustful harangue.

“In this new book life is represented as anarchic horniness on the rampage against death and its harbingers, old age, and impotence,” Frank Kermode wrote in The New York Review of Books, adding, “There is really only one way for him to tell the story — defiantly with outraged phallic energy.”

Like “Portnoy’s Complaint,” “Sabbath’s Theater” seemed to liberate its author, and yet the work that followed — what Mr. Roth called his American trilogy: “American Pastoral,” “I Married a Communist” and “The Human Stain” — is less about sex than about history or traumatic moments in American culture. Zuckerman returns as the narrator of all three novels, but he is in his 60s now, impotent and suffering from prostate cancer. His prose is plainer, crisper, less show-offy, and he is less an actor than an observer and interpreter.

The books are full of dense reportorial detail — about such seemingly un-Rothian subjects as glove making and ice fishing — as they tell Job-like stories. There is Swede Lvov, a seemingly gilded Newark businessman, a gifted athlete married to Miss New Jersey of 1949, whose life is destroyed in the 1960s when his teenage daughter becomes an antiwar terrorist and plants a bomb that kills an innocent bystander. Ira Ringold is a star of a radio serial during the McCarthy era who is blacklisted and becomes the subject of

These books are not without their comic moments, but history here is no joke; it is more nearly a tragedy. In 2007, Mr. Roth killed Zuckerman off in the sad and affecting “Exit Ghost,” a novel that cleverly echoes and inverts the themes of “The Ghost Writer,” the first of the Zuckerman novels.

That work set the tone for the rest: “Indignation” (2008), a ghost story of sorts about a young student unfairly expelled from college and sent off to fight in the Korean War; “The Humbling” (2009), about an actor who has lost his powers; and “Nemesis,” about the polio epidemic of the 1950s. The prose became even sparer and, in the case of “Nemesis,” deliberately matter-of-fact and unliterary, and though the books have plenty of sexual moments, they are haunted by something darker and bleaker.

Yet the very existence of these books, coming reliably almost one every year, seemed to belie their message. “Time doesn’t prey on my mind. It should, but it doesn’t,” Mr. Roth told David Remnick. He added: “I don’t know yet what this will all add up to, and it no longer matters because there’s no stopping. All you want to do is

Increasingly, Mr. Roth spent most of his time alone in his 18th-century Connecticut farmhouse, returning to New York mostly in the winter when he grew so stir-crazy he found himself talking to woodchucks. He worked, read in the evenings (nonfiction mostly) and occasionally listened to a ballgame. In some ways he came to resemble his own creation, Nathan Zuckerman, who asks at the end of a chapter in “Exit Ghost,” “Isn’t one’s pain quotient shocking enough without fictional amplification, without giving things an intensity that is ephemeral in life and sometimes even unseen?”

“Not for some,” he goes on. “For some very, very few that amplification, evolving

In 2010, right after “Nemesis,” Mr. Roth decided to quit writing. He didn’t tell anyone at first, because, as he said, he didn’t want to be like Frank Sinatra, announcing his retirement one minute and making a comeback the next. But he stuck with his plan and in 2012, he officially announced that he was done. A Post-it note on his computer said, “The struggle with writing is done.”

He had been famous for putting in endless days at his stand-up desk, throwing out more pages than he kept, and in a 2018 interview, he said he was worn out. “I was by this time no longer in possession of the mental vitality or the physical fitness needed to mount and sustain a large creative attack of any duration.” He settled into the contented life of an Upper West Side retiree, seeing friends, going to concerts.

He was in frequent communication with his appointed biographer, Blake Bailey, whom he sometimes flooded with notes, and he was also at pains to straighten out an erroneous Wikipedia account of his life. Mostly, he read — nonfiction by preference, but he made